in conversation with slinat (silly in art)

Paintings in the Slinat studio, Bali

Your work consistently deconstructs archival photographs from the Dutch colonial era in Bali. What does this allow you to express that contemporary photography cannot?

If colonial photographs are shown without intervention, they reproduce a romantic narrative that has long been used by the tourism industry, beginning in the 1920s. By deconstructing these images, I attempt to reveal perspectives of equality, environmental issues, and cultural tensions that have become daily realities in Bali.

Your titles such as Save Your Culture, Sell Your Land carry strong social messages. How do you determine when a title must guide the viewer?

Sometimes a specific issue feels urgent and requires clarity. At other times, I begin drawing and the right title emerges naturally. Often, ideas come during research into colonial era photographs the image itself suggests the direction.

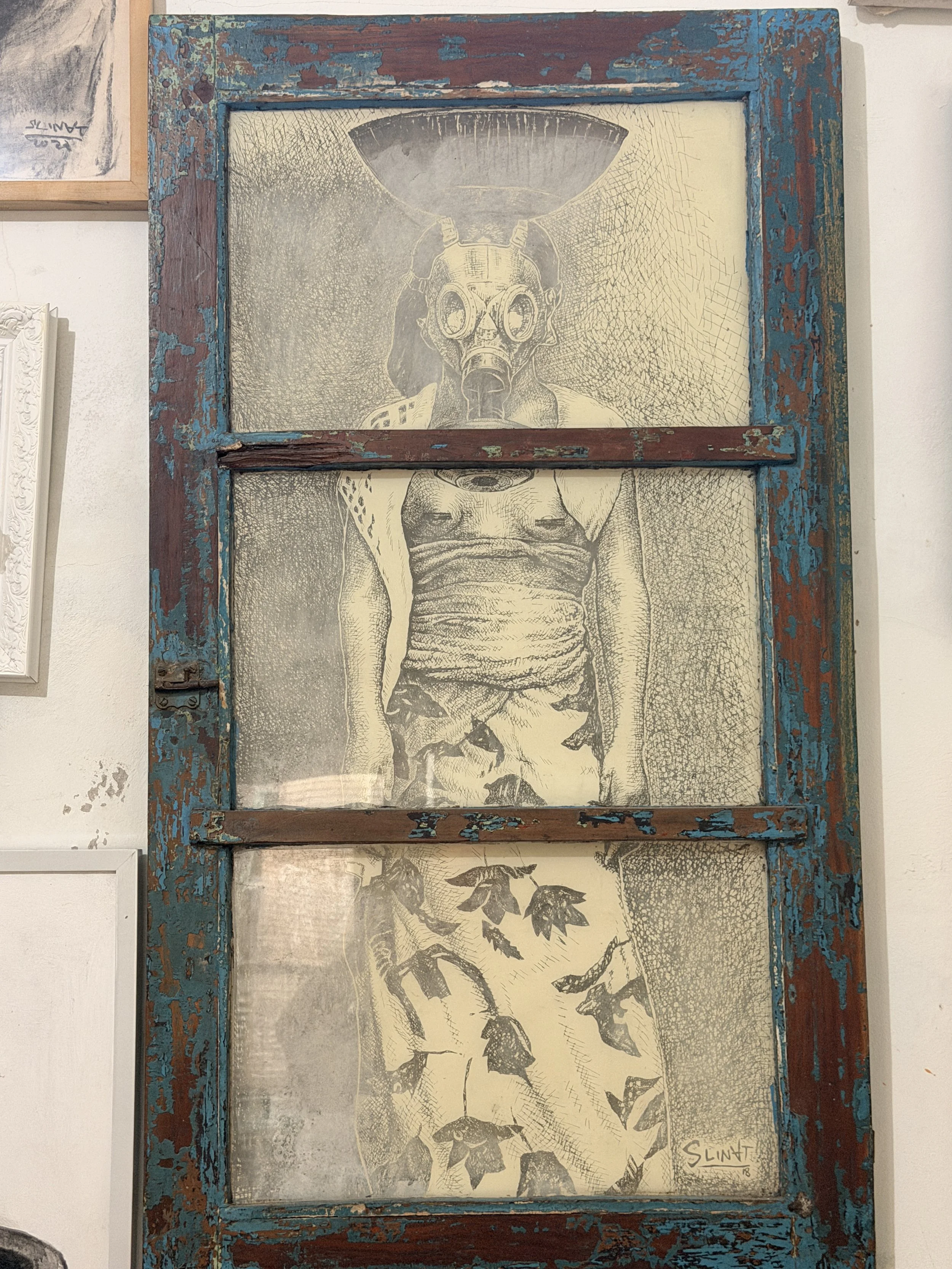

Painting on a glass window, Slinat

You frequently work with charcoal, tobacco extract, and found materials. How do these materials connect to Bali’s history and transformation?

Charcoal connects to the traditional Balinese Sigar Mangsi technique used in wayang painting. I believe the technical process should align with the theme. When speaking about Bali, it feels essential to use techniques rooted in Balinese culture.

With found materials, I also respond to environmental concerns. I leave traces of the object’s previous life a window frame, a brand name on cardboard so its history remains visible. Each era produces its own objects; my hope is that future production will be more environmentally responsible.

How important is it to integrate traditional techniques into contemporary critique?

It is fundamental. Sigar Mangsi uses natural charcoal derived from simple materials such as twigs. Its subtle visual language influenced me deeply. I was also inspired by the Balinese artist Murniasih, who brought this technique into contemporary practice. Tradition strengthens the critical voice.

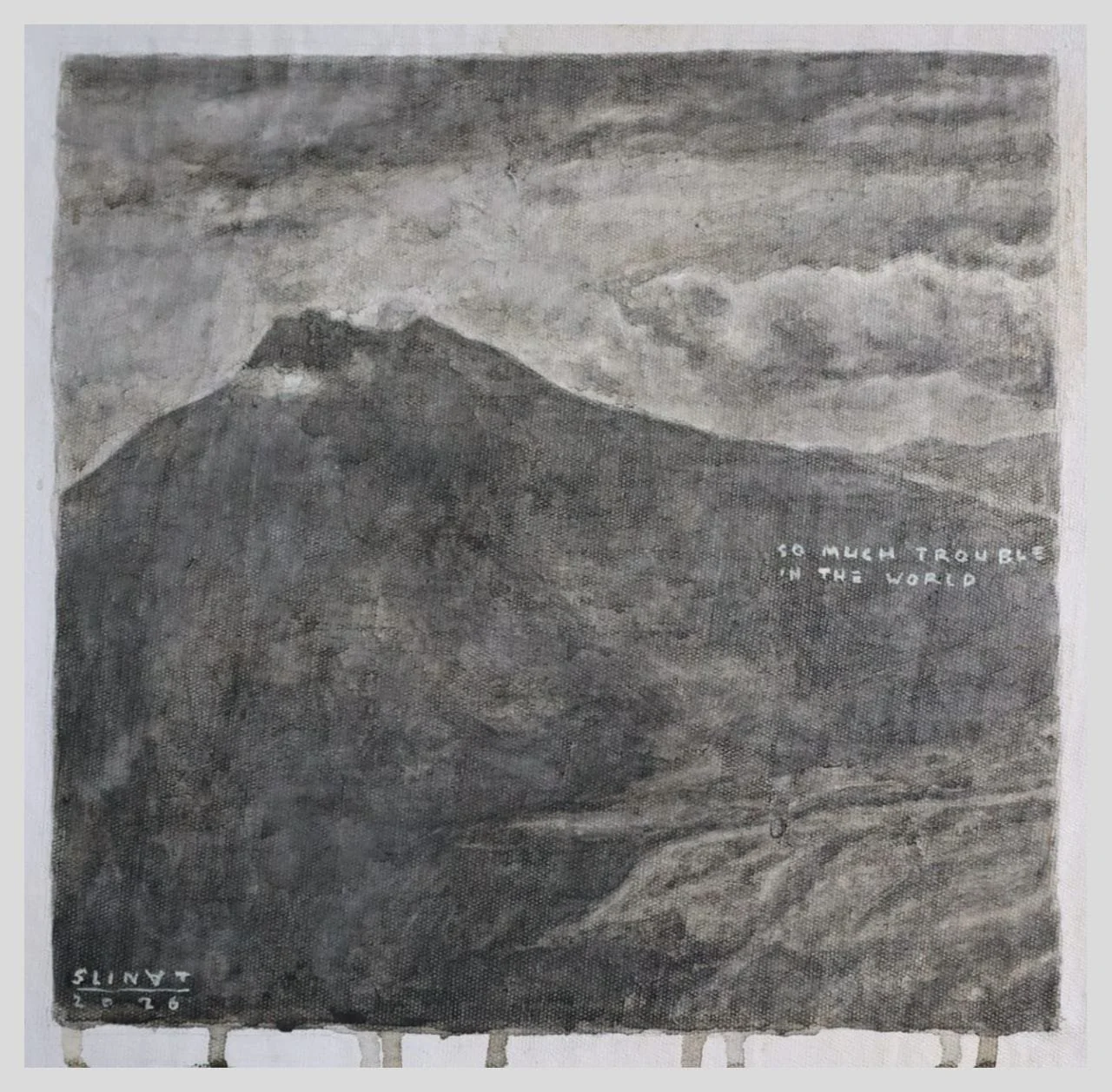

“There is no stage” Slinat

Are works such as Gray Landscape a protest, documentation, or something else?

They depict transformation. Landscapes once open and agricultural are now buildings. Lumbung structures once used to store rice have become villas. These changes reflect narrowing rice fields and reduced harvests. My work reflects this shift without romanticizing it.

Your figures often wear gas masks. What role do they play?

They contrast the exotic image of Bali with today’s complex reality. They represent modern Balinese life — working continuously, balancing economic necessity and cultural obligations. They summarize tourism history, social inequality, and environmental pressure.

Does the meaning of your work change between public space and private collections?

The work remains the same. What changes is the audience. Public space allows unlimited interaction. Institutional and private collections offer another context for reflection. Both are important.

“A relaxing view” Slinat

How do international audiences respond?

Many recognize similar patterns in their own regions tourism driving up land prices, forcing locals to relocate. Some are surprised because their perception of Bali was shaped only by tourism imagery. Sharing this narrative is not about criticism, but about building something more just.

How would you like your body of work to be read in the future?

As a summary of Bali’s tourism history, social inequality, cultural tension, and environmental challenges. Art is another way of speaking about daily realities.

What do you hope collectors understand when they acquire your work?

I hope they understand the story behind it and perhaps feel encouraged to respond to that story in meaningful ways.